This is a multi-part post:

- Part 1 establishes terminology (tasks, threads and processes and how they relate to concurrency and parallelism) and gives an overview of challenges faced in concurrent programming.

- Part 2 (this article) shows what can go wrong when using threads without synchronization and explains the role and effects of the Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) in Python.

- Part 3 (TODO) explains some common thread synchronization primitives, accompanied by Python examples.

- Part 4 (TODO) explains some common process synchronization primitives (inter-process communication mechanisms), accompanied by Python examples.

- Part 5 (TODO) tackles parallel algorithm design and performance evaluation.

Threads

Remember from our last post that threads are the smallest set of instructions that can be managed by the scheduler. Unlike processes, multiple threads of a program share the same address space and are capable of accessing the same data.

Each thread has its own program counter and registers. The program counter is a special register that tracks the instruction that is currently being executed (or the next instruction to be executed). When the scheduler switches between two threads running on a single CPU, a context switch takes place in which the state of the registers of the thread being switched from are stored and the registers of the thread being switched to are restored.

Here’s an inspirational quote from OSTEP (Remzi H. Arpaci-Dusseau and Andrea C. Arpaci-Dusseau, chapter 26, Concurrency and threads) to get us started:

Computers are hard enough to understand without concurrency. Unfortunately, with concurrency, it simply gets worse. Much worse.

In Python, we can create and manage threads using the threading module. In the following example we create and start two threads that run the method my_task() (which essentially does nothing of interest beside sleep for a given amount of time):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

import threading

import time

def my_task(x, y):

print('{} got x={}, y={}'.format(threading.current_thread().getName(), x, y))

time.sleep(x + y)

print('{} finished after {:.2f} seconds'.format(

threading.current_thread().getName(), x + y))

def main():

thr1 = threading.Thread(target=my_task, name='Thread 1', args=(1, 2,))

thr2 = threading.Thread(target=my_task, name='Thread 2', args=(.1, .2,))

thr1.start()

thr2.start()

thr1.join()

thr2.join()

print('Main thread finished')

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

In main(), we create the threads, then actually start() them, and finally join() them. Joining a thread means to wait until it terminates. Unsurprisingly, here is the output of the above program:

1

2

3

4

5

Thread 1 got x=1, y=2

Thread 2 got x=0.1, y=0.2

Thread 2 finished after 0.30 seconds

Thread 1 finished after 3.00 seconds

Main thread finished

Why do we need synchronization?

But everything works fine. Why do we need synchronization? Glad you’ve asked! Concurrency can be tricky. Remember that we have discussed some common concurrency pitfalls in Part 1 of this series. It might have all seemed a bit abstract, so let us now look at an example where things don’t go according to plan. Suppose we have two threads and each one increments a global counter:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

import threading

counter = 0

def increment(n):

global counter

for _ in range(n):

counter += 1

def main():

thr1 = threading.Thread(target=increment, args=(500000,))

thr2 = threading.Thread(target=increment, args=(500000,))

thr1.start()

thr2.start()

thr1.join()

thr2.join()

print(f'counter = {counter}')

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

The result is not what we expect. Even worse, it is inconsistent from run to run:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

$ python 02_b_sum_without_synchronization.py

counter = 793916

$ python 02_b_sum_without_synchronization.py

counter = 1000000

$ python 02_b_sum_without_synchronization.py

counter = 697999

$ python 02_b_sum_without_synchronization.py

counter = 872864

Let us understand what just happened:

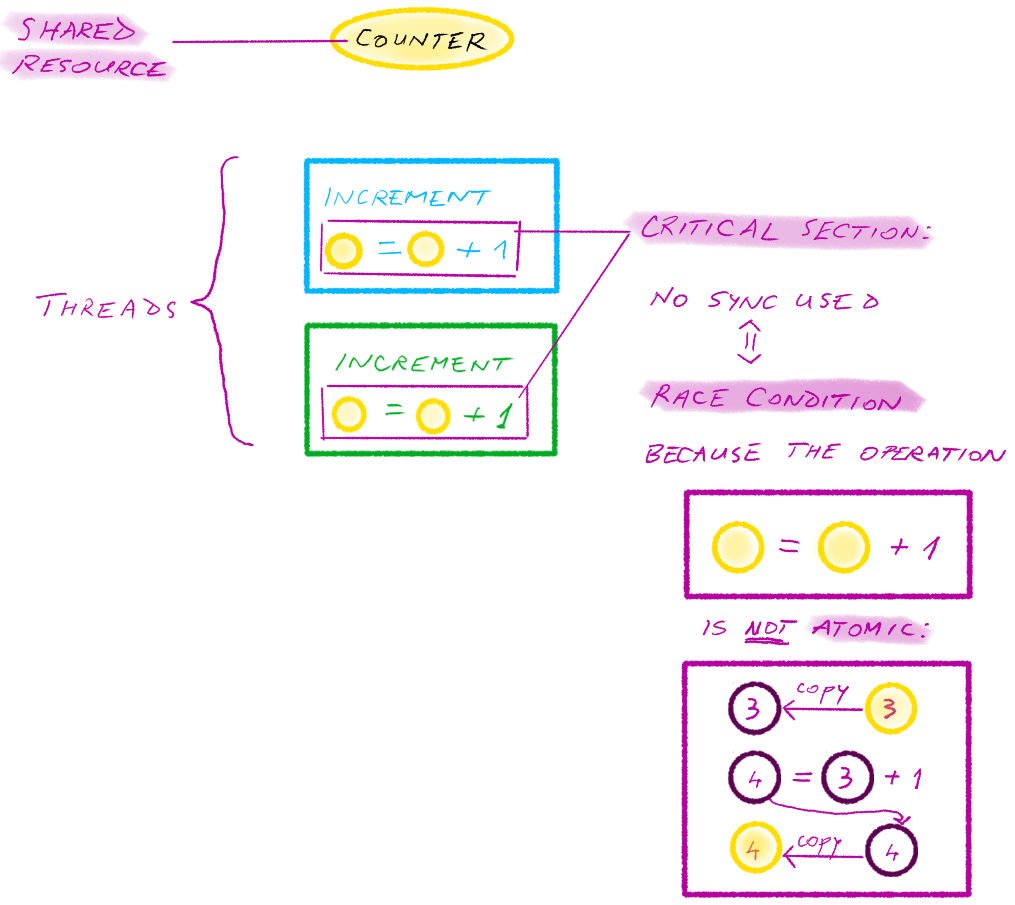

Critical section

A critical section refers to code that can result in a race condition when executed by multiple threads, because a a shared resource is involved.

In our example, both threads attempt to modify the global counter variable by incrementing it. In other words, both threads access a shared resource in a critical section in write mode, without using thread synchronization.

Race condition

A race condition occurs when several threads execute a critical section without synchronization mechanisms in place. Depending on the order in which the threads execute the critical section, the result of the program is different.

In our example, both threads attempt to increment the global counter; as we’ve seen, not all increments are successful.

Atomic operations

A series of actions is atomic if the actions are “all or nothing”, meaning they either all occur, or none occur. (You might be familiar with database transactions: by definition, they are atomic.)

In our example, increments do not succeed because the increment operation itself is not atomic. Suppose the counter contains the value 3. In order to increment it, the first step is to read its current value (3) into a temporary location. The second step is to increment this temporary value (it now becomes 4). The final step is to copy the new value from the temporary location (4) into the counter. However, if a second thread accesses the counter concurrently, it can change its value while the “lagging” thread uses the stale value from the temporary location.

This problem can be solved by rendering critical sections atomic through thread synchronization primitives such as locks or semaphores. What we mean by that is that we allow one thread to execute the critical section while the others are denied access to the critical section until the thread that is in control releases it. We will look into thread synchronization primitives in detail in the next post.

Thread communication

Apart from thread synchronization, concurrency can also involve thread communication. While thread synchronization and thread communication are related, in thread communication the focus is shifted to threads waiting on other threads to finish before executing. In the next part of this series we will see how condition variables help us achieve thread communication.

The Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) in Python

Now that we’ve seen why thread synchronization is necessary, we cannot simply jump right in without first mentioning the dreaded Python GIL, short for the Global Interpreter Lock.

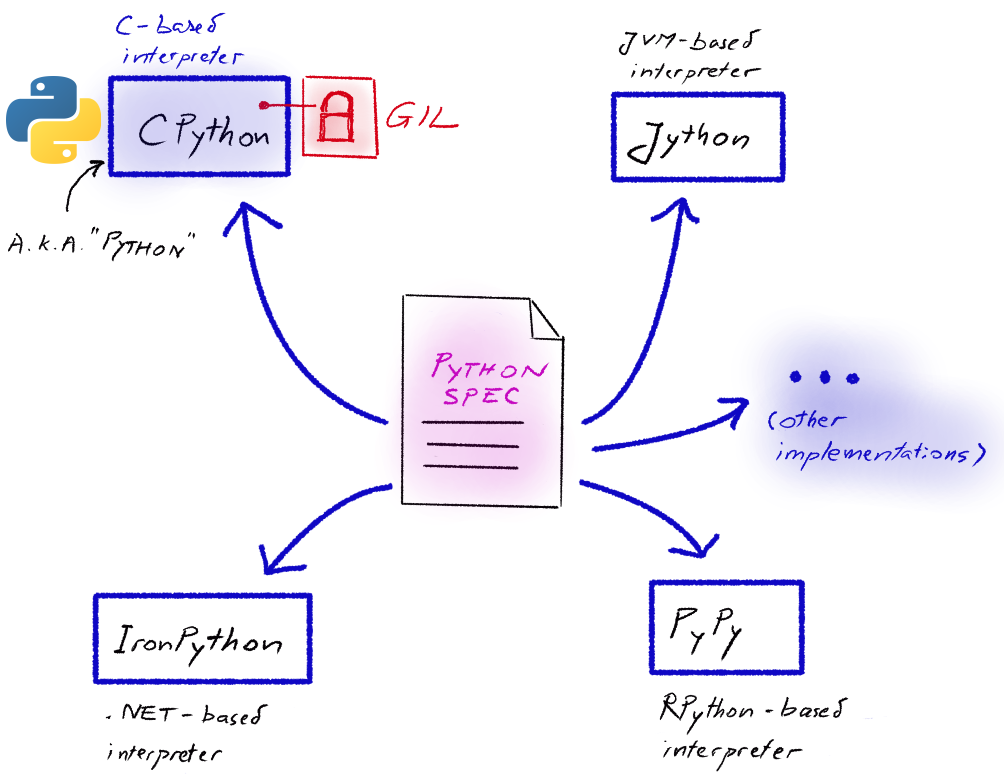

Python interpreters

Before properly defining the GIL, we need to take a step back and talk about… Python. In the strictest sense, Python is “just” a programming language specification. Python interpreters are different implementations of the Python language specification. The most popular implementation is CPython (written in C), commonly called python by language abuse. Alternative Python implementations exist.

The image below summarizes the relationship between language specification and implementation:

CPython and the GIL

When we run a Python script using the python (i.e. CPython) interpreter, the source code is first compiled into byte code, a low-level platform-independent representation that is executed by the Python virtual machine. You have probably already seen the .pyc files in the __pycache__ directory – that is byte code. The Python virtual machine is not a separate component, but rather a loop running inside the Python interpreter. It simply executes the generated byte code line by line.

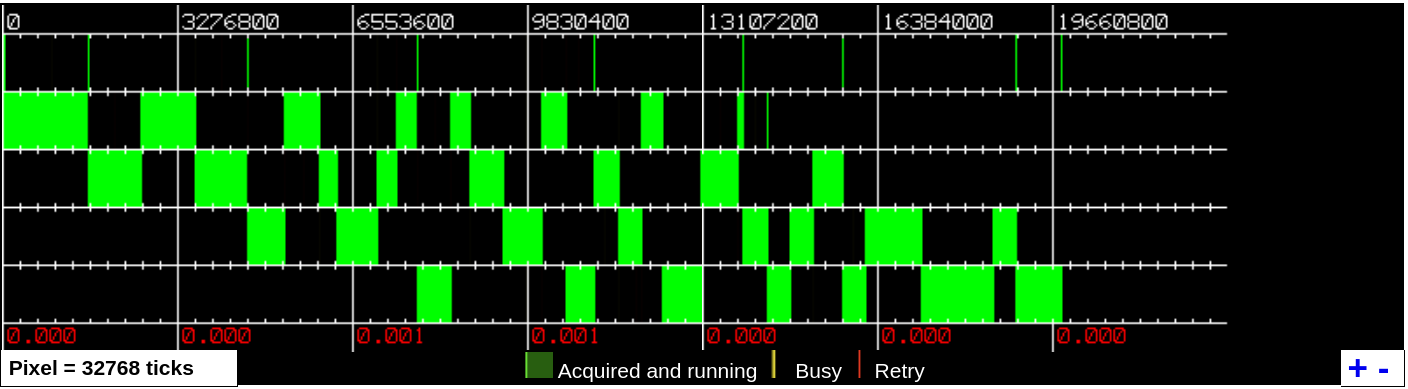

The GIL is a mechanism that limits Python (remember we’re talking about the CPython interpreter) to execute only one thread at a time. Below you can see a GIL visualisation showing the main thread and 4 additional threads running on a single CPU; the green blocks represent the time when threads are executing:

The reason behind the GIL

Why would Python designers restrict the CPython interpreter to only be able to execute a single thread at a time? When CPython was being developed, its garbage collector was designed to use reference counting. This means that an object is released from memory when its reference count reaches zero.

We can get the reference count of an object in memory using sys.getrefcount(). In the example below, notice that when we assign the object to a new variable, the reference count increases:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

In [46]: import sys

In [47]: z = "this is a string variable"

In [48]: sys.getrefcount(z)

Out[48]: 8

In [49]: z2 = z

In [50]: sys.getrefcount(z)

Out[50]: 9

If several threads are running, race conditions may modify the reference count if it is not protected by a simple synchronization mechanism called “lock” (that we will be looking into in the next post). The solution was to impose a global lock providing exclusive access to the Python interpreter. This way, the Python interpreter executes byte code using the GIL, which in turn means that only one thread is active at any given time. The advantage is that reference counting becomes thread-safe. The drawback is that the remaining threads from the byte code must wait for the GIL to become available.

You can also check out the article over at RealPython for more context.

Effects of the GIL

The dreaded effect of the Python GIL that we’ve hinted at earlier is that, no matter how many CPUs there are, since only a single thread can run at a time, the extra CPU cores remain unused. In other words, I/O-bound problems can be sped up through multithreading, albeit the threads run one at a time, in interleaved fashion. However, because the GIL prevents threads from running in parallel, no speed-up is possible unfortunately for CPU-bound problems (which, as we’ve seen in Part 1, require parallel execution).

Do not despair though: multiple CPUs can be used in Python if we create processes instead of threads. Since every process comes with its own interpreter, the GIL issue is effectively side-stepped. We will be looking into processes in a later article in this series.

Conclusion

In this post we’ve seen:

- How to launch separate threads in Python

- That launching threads without synchronizing them is rarely a good idea. We need to:

- control how threads access a critical section

- have threads wait on other threads to finish

- How the Python GIL (Global Interpreter Lock) complicates things further by only allowing a single thread to be active at a time

The next post in this series will present thread synchronization primitives and show how they can be used in Python. In subsequent posts we will also be discussing processes, asynchronous programming, as well as parallel algorithm design and evaluation.

Resources

threading(Python documentation)- Garbage collection (Wikipedia)

- Python GIL visualizations (David Beazley)

- Global Interpreter Lock (Python wiki)

- Global Interpreter Lock (Abhinav Ajitsaria @ RealPython, 2018)

- Operating systems: Three easy pieces (Arpaci-Dusseau & Arpaci-Dusseau)

- Python concurrency for senior engineering interviews (educative.io course)

Comments powered by Disqus.