This is a multi-part post:

- Part 1 (this article) establishes terminology (tasks, threads and processes and how they relate to concurrency and parallelism) and gives an overview of challenges faced in concurrent programming.

- Part 2 shows what can go wrong when using threads without synchronization and explains the role and effects of the Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) in Python.

- Part 3 (TODO) explains some common thread synchronization primitives, accompanied by Python examples.

- Part 4 (TODO) explains some common process synchronization primitives (inter-process communication mechanisms), accompanied by Python examples.

- Part 5 (TODO) tackles parallel algorithm design and performance evaluation.

I’m writing this for my frustrated past self, who couldn’t wrap her head around these concepts. Moreover, my future self will likely benefit as well (I’m inferring this by extrapolating my current self’s goldfish-grade memory). And last but not least, I’m also writing this post for anybody out there still struggling. ![]()

Tasks, processes and threads

First things first: let’s establish some terminology.

Not everybody agrees on the definition of a task, but this term is so ubiquitously used that it is worth mentioning. A task refers to a set of instructions that are executed. For the purpose of this post, tasks can be seen as roughly equivalent to functions of a computer program.

A thread is the smallest set of instructions that can be managed by a scheduler. At the operating system (OS) level, a scheduler assigns resources (e.g. CPUs) to perform tasks.

A process is an instance of a running program. A process has at least one thread. However, programs can spawn multiple processes (e.g. a webserver may have a master process and several worker processes). To complicate things further, it is also possible to launch multiple instances of the same program (e.g. your favorite text editor).

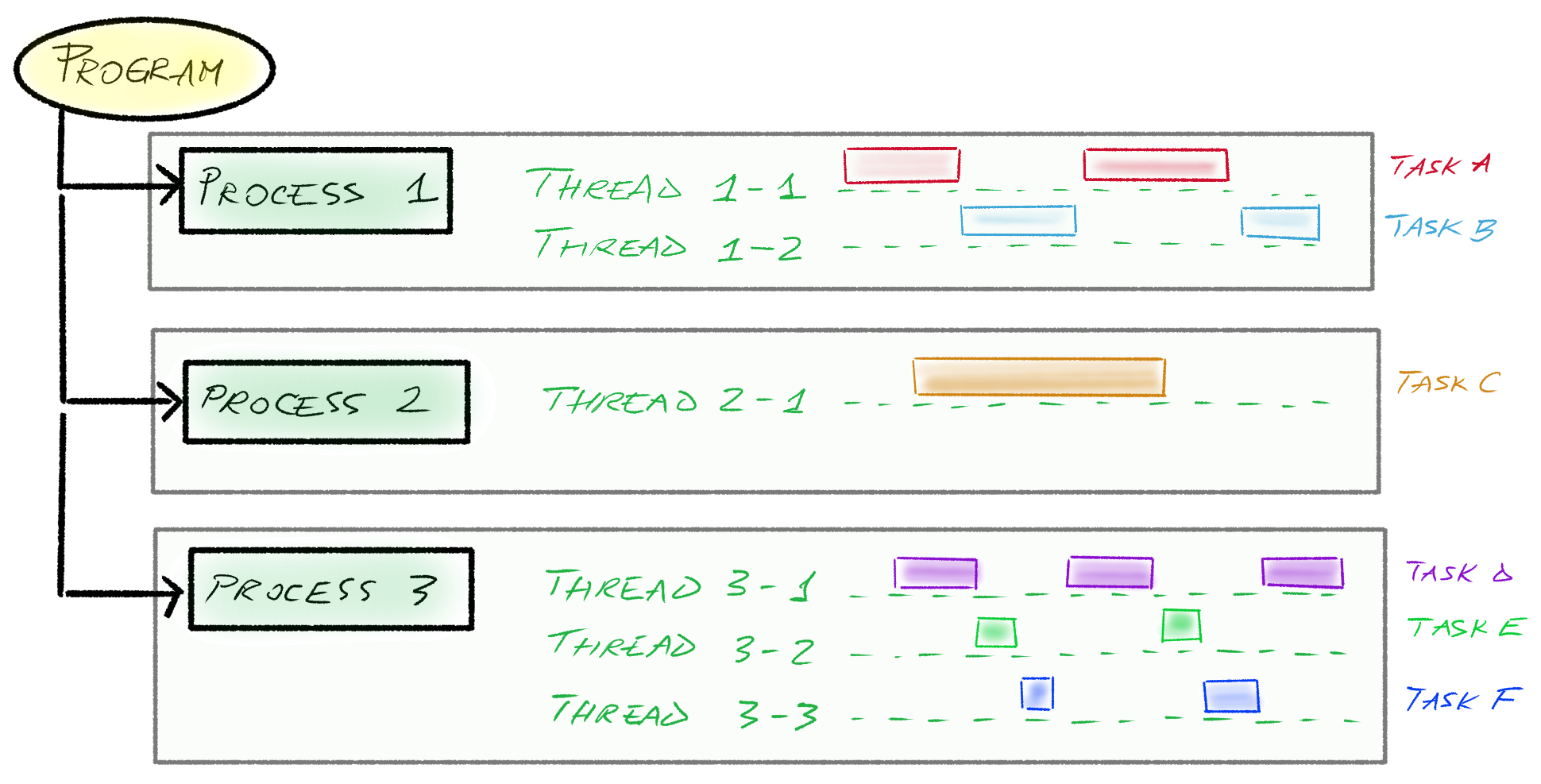

I will attempt to give a more intuitive understanding of these terms in the following figure:

In this example, we have a program that launches three processes. Processes 1, 2 and 3 have 2, 1, and 3 threads, respectively. Each thread runs a given task A through F.

There is an important distinction to consider: the threads of a given process all share that process’s address space, but come with their own stacks and registers. In other words:

- A thread has its own stack and registers

- A thread has access to the code, data and resources of its owner process

Therefore, in terms of resource sharing:

- Threads (of a given process) share the same resources. Care must be taken as to how threads access those resources. Thread synchronization primitives such as condition variables, semaphores, mutexes or barriers allow to control the way in which threads access shared resources and will be discussed in a future post.

- Processes do not share the same resources, by default. Process synchronization, also known as Inter-Process Communication (IPC), must be used if resource sharing is necessary. Some of the most common mechanisms for achieving IPC are signals, sockets, message queues, pipes and shared memory. IPC will be discussed in a future post.

It is worthwhile to note that thread creation is lightweight in comparison to spawning a new process. This is an added benefit to the fact that threads have access to shared resources in the address space of their owner process.

How are tasks executed with respect to one another? How are processes executed with respect to the CPUs? Here’s where the next part comes in, where we discuss concurrency vs parallelism.

Concurrency and parallelism

Here’s what Rob Pike (best known as being one of the three creators of the Go programming language) has to say (slides, talk):

Concurrency is about dealing with lots of things at once. Parallelism is about doing lots of things at once. Not the same, but related.

He also goes on to say:

Concurrency is about structure, parallelism is about execution. Concurrency provides a way to structure a solution to solve a problem that may (but not necessarily) be parallelizable.

(emphasis mine)

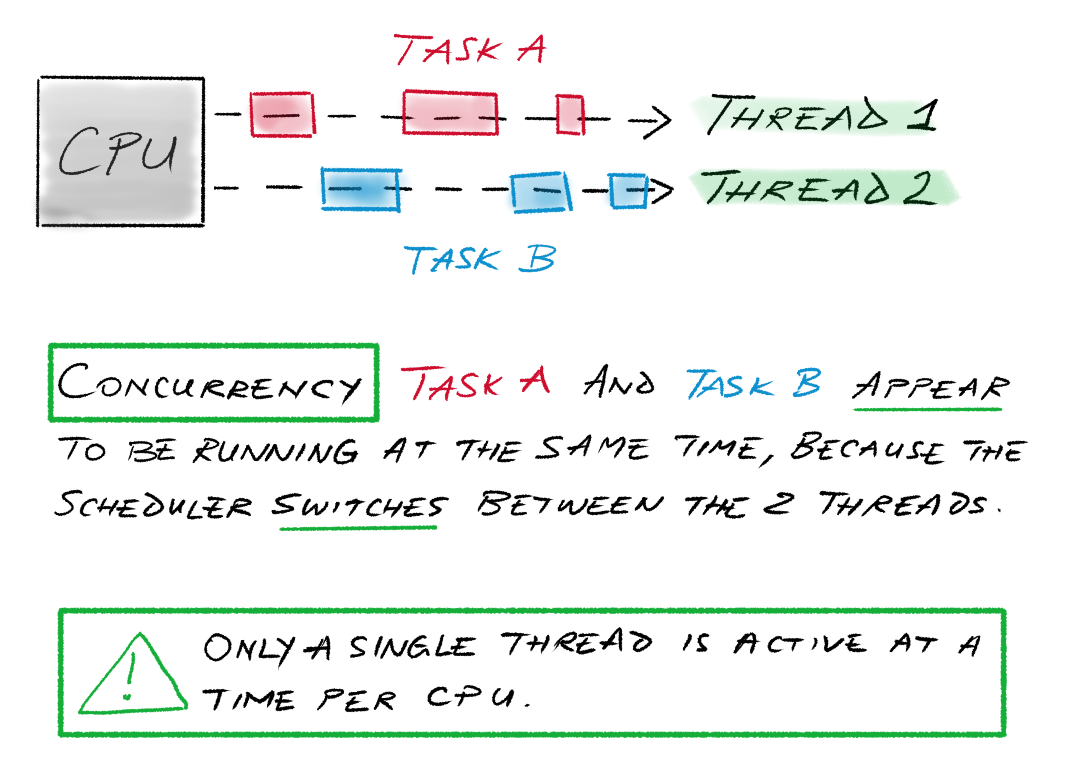

In operating system terms, the “things” Rob Pike refers to are tasks. Concurrency simply means that the operating system will schedule the tasks to run in an interleaved fashion, thus creating the illusion of them being executed at the same time:

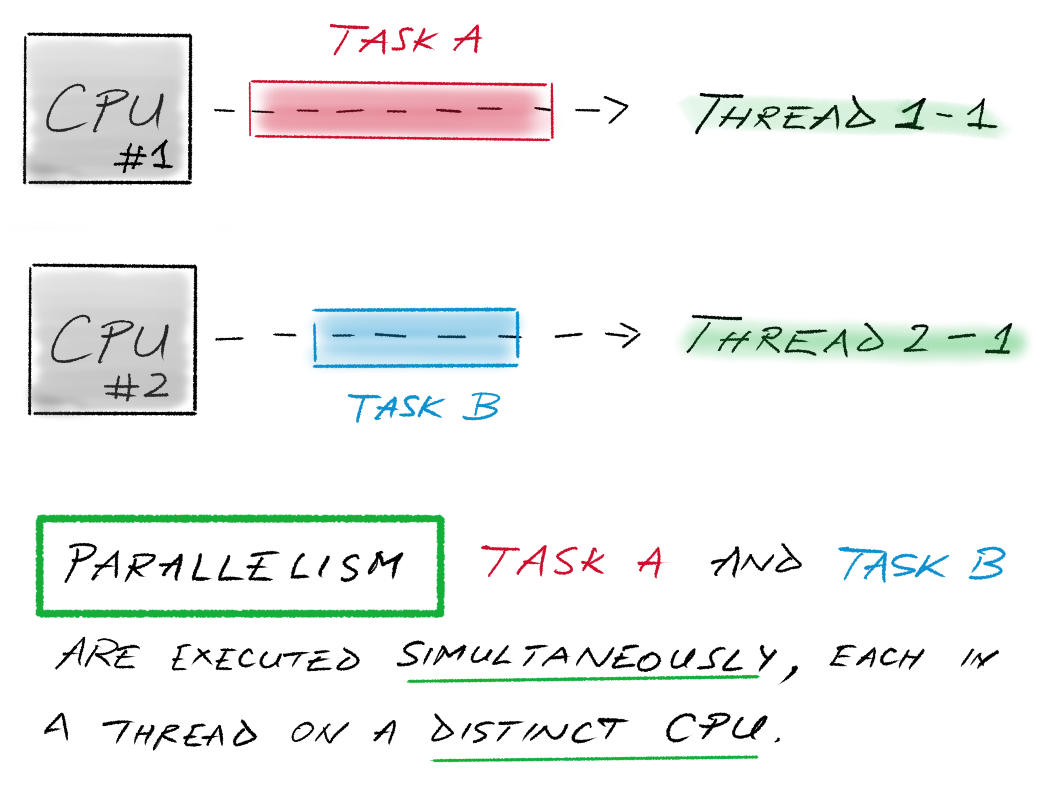

Whereas parallelism means that tasks are run on actually distinct CPUs:

Make sure to also check out Jakob Jenkov’s post on concurrency vs parallelism to get a broader picture (and to see how he defines parallelism in a stricter sense than what I have conveyed here).

What is concurrency used for?

Concurrency is useful for two types of problems: I/O-bound and CPU-bound.

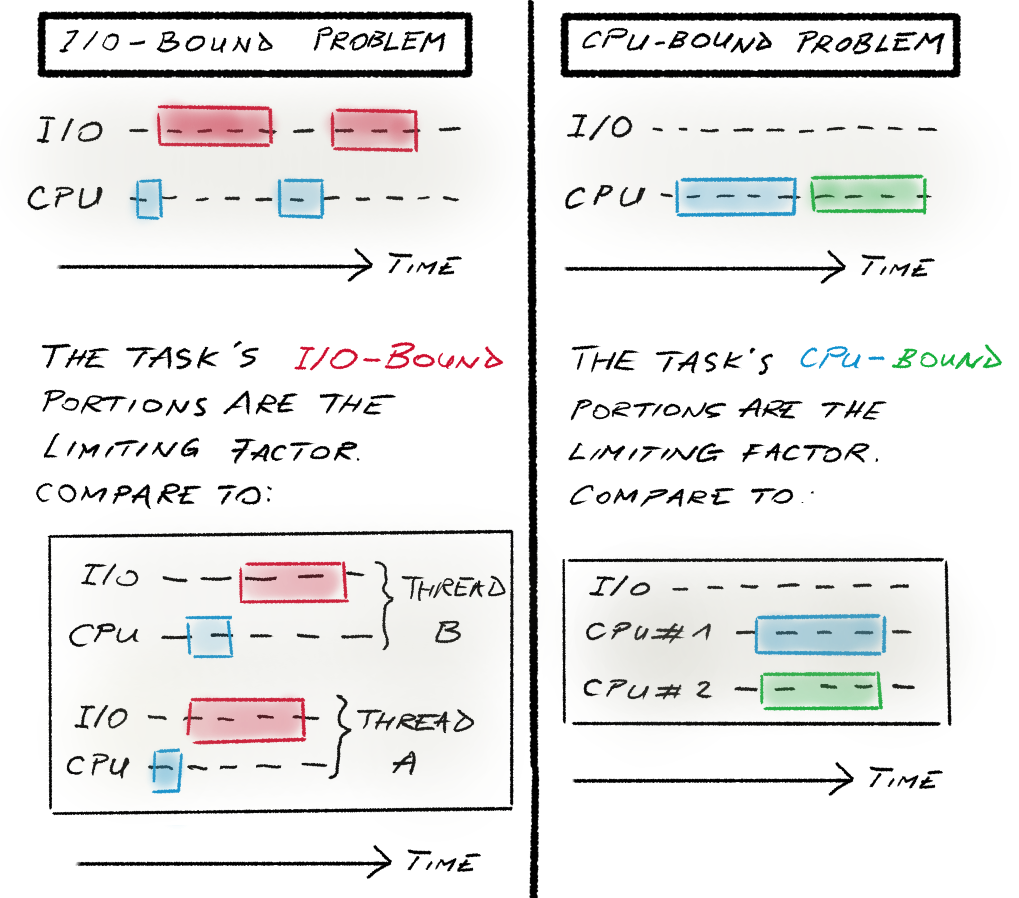

I/O-bound problems are affected by long input/output wait times. The resources involved may be files on a hard drive, peripheral devices, network requests, you name it. In the above diagram, red blocks show how much time is spent for I/O operations. When downloading files from the internet, for instance, an important speedup can be attained if we download concurrently instead of sequentially. The speedup comes from overlapping the I/O-bound wait times (the red blocks in the diagram). Therefore, concurrency (launching more threads) can improve I/O-bound problems.

For CPU-bound problems, on the other hand, the limiting factor is the CPU speed. These are generally computational problems. If such programs can be decomposed into independent tasks (with the typical example being matrix multiplication), then an important speedup can be attained if we throw more CPUs at the problem. Therefore, parallelism (launching more processes) can improve CPU-bound problems.

Challenges in concurrent programming

Writing a concurrent program is more difficult than writing its sequential version. There are many things to consider and account for. Often times, isolation testing is a nightmare. Here we will discuss some of the most common challenges.

Race condition

A race condition leads to inconsistent results that stem from the order in which threads or processes act on some shared state.

For example, suppose the shared state is the string "wolf". We have two threads, each prefixing the shared state with a different word: thread A prefixes the shared string with "bad" and thread B prefixes it with "big".

- If A runs before B, the shared state becomes

wolf => bad wolf => big bad wolf - If B runs before A, the shared state becomes

wolf => big wolf => bad big wolf

We can try to isolate race conditions using sleep() statements that will hopefully modify timing and execution order.

Race conditions occur because access to the shared state happens outside of synchronization mechanisms. A possible mitigation strategy is to use barriers (see the next post in the series on Thread synchronization primitives).

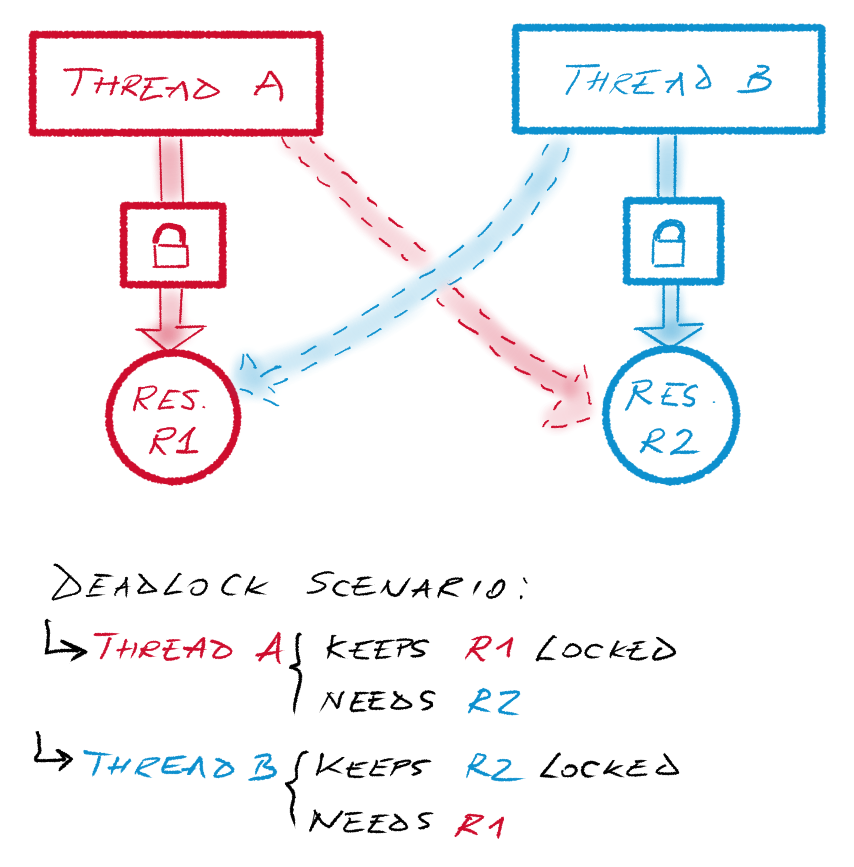

Deadlock

A deadlock occurs when several tasks are blocked indefinitely while holding a shared resource and while waiting for another one.

Deadlocks occur when the Coffman conditions below are satisfied simultaneously:

- Mutual exclusion: at least two shared resources are held without sharing them with other tasks.

- Hold and wait: a task that holds a resource is requesting another resource which is held by another task.

- No preempt: the task is responsible to release the resource voluntarily.

- Circular wait: each task is waiting for a resource that is held by another task, for all tasks involved up to the last one which is, in turn, waiting for a resource held by the first task.

Livelock

A livelock is similar to a deadlock: it involves tasks that need at least two resources each, however none of them is blocked. Unlike a deadlock, tasks in a livelock are overly polite: they acquire a resource, they test whether another resource is available, they release the first resource if the second one is not available, wait for a given amount of time, then repeat the whole process all over again. If bad timing is involved, none of the tasks involved in a livelock can ever progress. The irony is that livelocks often occur while attempting to correct for deadlocks…

Starvation

Resource starvation occurs when a task never acquires a resource it needs. It can usually be resolved by improving the scheduling algorithm such that tasks that has been waiting for a long time get assigned a higher priority.

Priority inversion

Priority inversion occurs when a task with low priority holds a resource required by a task with high priority. This results in the low-priority task finishing before the high-priority task. It can also get more subtle than this, involving a task with medium priority that preempts the low priority task, thus indirectly blocking the high-priority task indefinitely. Several protocols can be used to avoid priority inversion, one of them being priority inheritance. This is how the Mars Pathfinder priority inversion bug from 1997 was fixed.

Conclusion

This post takes a bird’s eye view of concurrency by:

- Establishing some necessary terminology (task, thread, process, concurrency, parallelism)

- Taking a look at two classes of problems (I/O-bound and CPU-bound) and how they relate to concurrency

- Explaining some common pitfalls in concurrent programming (race conditions, deadlock, livelocks, starvation and priority inversion)

The next posts in this series will illustrate synchronization primitives (for threads and processes), list principles to keep in mind when designing concurrent programs, and show how to evaluate parallel implementations.

Resources

- Concurrency vs parallelism (Jakob Jenkov)

- Concurrency is not parallelism (Rob Pike, 2012) [slides]

- Concurrency is not parallelism (Rob Pike, 2012) [talk]

- Inter-process communication (Wikipedia)

- Priority inversion

Comments powered by Disqus.