The problem

In the previous post on parallelism in Python, we have seen how an external Python script performing a long computation can be ran in parallel using Python’s multiprocessing module. If you haven’t done so already, take your time to read that post before this one.

Here we elaborate on the scenario presented in the previous post:

- As before, we have an external Python script

worker.pythat performs a long computation. - As before,

worker.pyis launched several times in parallel using a multiprocessing pool. - As before, the computations performed by the different worker instances are independent from each other.

- Here comes the novelty: although the different computations are independent, they need to access (read and update) a shared resource.

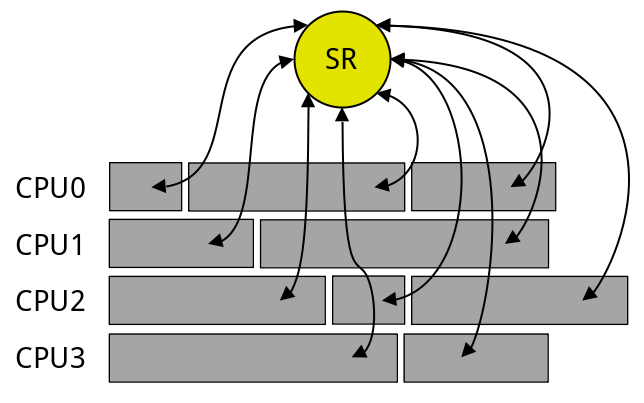

The figure below shows a shared resource (SR) in yellow, that needs to be accessed by the tasks in grey (arrows). Some tasks are ran in parallel on the four available CPUs.

What we need to do is enable each task to access the shared resource only if no other task is currently accessing it. This can be achieved by using a synchronization mechanism called a lock.

The worker script

First let us briefly see what is the task that we will be running in parallel. The worker.py script does just that, it performs a long “computation” (sleeping) and outputs a message at the end (for more explanations see the previous post):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

import sys

import time

def do_work(n):

time.sleep(n)

print('I just did some hard work for {}s!'.format(n))

if __name__ == '__main__':

if len(sys.argv) != 2:

print('Please provide one integer argument', file=sys.stderr)

exit(1)

try:

seconds = int(sys.argv[1])

do_work(seconds)

except Exception as e:

print(e)

The main script

What we will be doing now is launching 100 processes in parallel on as many threads as we have CPUs. Each process launches worker.py as a Python subprocess. As we have seen above, the worker script sleeps for a given number of seconds.

The shared resource

Here is where the shared resource come into play. At the end of each “computation”, the worker process accesses this shared resource in both read and write mode. For the purpose of this example, let us imagine the shared resource is a list of results. The worker process needs to read the resource and update it with a certain value only if the value is not yet present in the list.

Note: The more observant may argue that a list updated only with values that are not already included in the list is the equivalent of a set. This is correct, however:

- the Python

multiprocessingmodule only allows lists and dictionaries as shared resources, and- this is only an example meant to show that we need to reserve exclusive access to a resource in both read and write mode if what we write into the shared resource is dependent on what the shared resource already contains.

The script

Let us see the main script main.py right now and we’ll get into some details below:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

import subprocess

import multiprocessing as mp

from tqdm import tqdm

NUMBER_OF_TASKS = 100

progress_bar = tqdm(total=NUMBER_OF_TASKS)

def work(sec_sleep, processed_values, lock):

seconds = int(sec_sleep) % 10 + 1

command = ['python', 'worker.py', str(seconds)]

subprocess.call(command)

with lock:

if seconds not in processed_values:

processed_values.append(seconds)

def update_progress_bar(_):

progress_bar.update()

if __name__ == '__main__':

tasks = [str(x) for x in range(1, NUMBER_OF_TASKS + 1)]

pool = mp.Pool()

manager = mp.Manager()

lock = manager.Lock()

shared_list = manager.list()

for i in tasks:

pool.apply_async(work, (i, shared_list, lock,),

callback=update_progress_bar)

pool.close()

pool.join()

print(shared_list)

Explanation

Just like in the previous post, we define a pool of tasks that we want to parallelize. Although the aim is to eventually run 100 processes (NUMBER_OF_TASKS is 100, see lines 5 and 23), we cannot effectively run them all at the same time. For true parallelism, each task should be handled by a separate CPU, and the tasks should be ran at the same time. This is why we define the pool of tasks as holding as many processes as there are CPU threads at line 24 (this is the default behavior for mp.Pool() with no argument). If you want to specify a different number of processes with respect to the available number of CPU threads you may use the cpu_count() method in the multiprocessing module or in the os module (for example, mp.cpu_count() - 1).

Once the multiprocessing pool is defined, we want to get stuff done. But before calling apply_async() on the pool’s processes, we first need to create both the shared resource that we’ve been talking about and the lock that will ensure that only one process may access the shared resource at a given time. Unlike in real life, if you want to get stuff done in Python’s multiprocessing module, you actually do need a Manager. We first create this manager, then use it to create the lock and the shared_list (lines 25-27).

In lines 29-31, we finally apply asynchronously the work() method to the pool of processes with the task at hand (i), the shared resource (shared_list) as well as the multiprocessing synchronization mechanism (lock). We use the callback update_progress_bar() in order to, well, update the tqdm progress bar.

Here is how the work() function handles the shared resource. It launches the external script worker.py using the Python subprocess module. The external script is ran with an argument representing the number of seconds (from 1 to 10) for which to run the long computation. Once the subprocess finishes, the work() method accesses the shared resource using the multiprocessing lock. In lines 13-15, the lock is acquired in order to ensure exclusive access to the shared list processed_values. Then if the number of seconds that the subprocess was called with is not already present in this list, we update the list with this value and we release the lock. Note that with lock is a shorthand notation for saying “acquire the lock before doing something, then do something, and finally release the lock after doing something”.

Parallelization in practice

Here is the output of our main.py script, truncated for brevity:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

$ python main.py

0%| | 0/100 [00:00<?, ?it/s]

I just did some hard work for 2s!

1%| | 1/100 [00:02<03:21, 2.04s/it]

I just did some hard work for 3s!

2%|█ | 2/100 [00:03<02:49, 1.73s/it]

I just did some hard work for 4s!

3%|█▊ | 3/100 [00:04<02:26, 1.51s/it]

I just did some hard work for 1s!

I just did some hard work for 5s!

5%|██▌ | 5/100 [00:05<01:54, 1.21s/it]

I just did some hard work for 6s!

6%|███▌ | 6/100 [00:06<01:47, 1.14s/it]

I just did some hard work for 2s!

I just did some hard work for 7s!

8%|████▎ | 8/100 [00:07<01:27, 1.05it/s]

I just did some hard work for 3s!

I just did some hard work for 8s!

10%|██████ | 10/100 [00:08<01:13, 1.23it/s]

[snip]

99%|██████████████████████████████████████████████████████ | 99/100 [01:12<00:01, 1.24s/it]

I just did some hard work for 10s!

100%|██████████████████████████████████████████████████████| 100/100 [01:14<00:00, 1.46s/it]

[2, 3, 4, 1, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]

Notice how several worker processes that have been sleeping for different amounts of time finish at the same time, for example between 3% and 5% there are two workers that finished: they respectively performed a 1s-long and a 5s-long computation.

The last line of the output shows the shared resource shared_list: it contains the amount of time in seconds for which the computations lasted, one item per amount of time, in the order in which the processes have been completed. No value appears twice.

This example shows that the execution of the worker.py script has been parallelized on several CPU threads and that every process successfully accessed the shared resource, by reading and updating it.

Further reading

subprocess(Python documentation)multiprocessing(Python documentation)- Parallel processing in Python (Frank Hofmann on stackabuse)

multiprocessing– Manage processes like threads (Doug Hellmann on Python Module of the Week)

Comments powered by Disqus.