The first time I had to explain to students why a C union may sometimes come in handy, I came up with this example. As my students had only been exposed to C for about 15 hours, I needed to refrain from talking about standard use cases involving low-level operations where unions are very useful.

The problem

Suppose we have 2D segments defined by their endpoints, like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

typedef struct {

double x;

double y;

} Point2D;

typedef struct {

Point2D start;

Point2D end;

} Segment;

Now, suppose we are required to write a function that will project a given segment on the horizontal (X) axis, and another one that will project the segment on the vertical (Y) axis. In most cases, the projection of a segment on either of the axes is another segment.

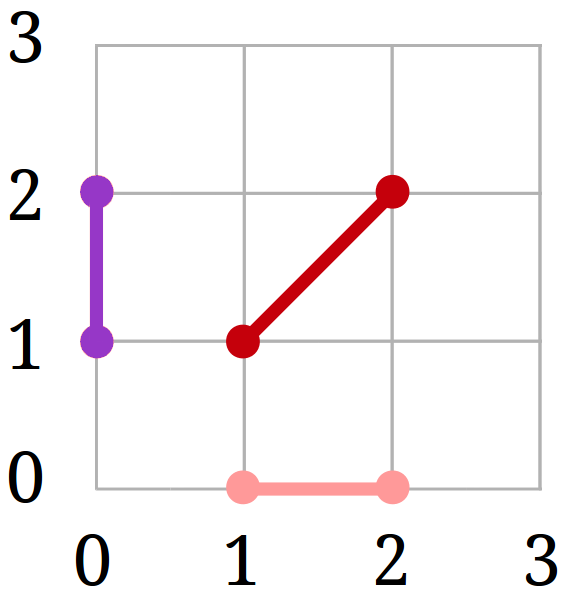

For example, in the figure at the right we have a segment with endpoints (1, 1) and (2, 2). (It will be referred to as “the red segment” later on.) Its projections on the X and Y axes will be:

For example, in the figure at the right we have a segment with endpoints (1, 1) and (2, 2). (It will be referred to as “the red segment” later on.) Its projections on the X and Y axes will be:

- The segment with endpoints (1, 0) and (2, 0) on the horizontal axis (in pink);

- The segment with endpoints (0, 1) and (0, 2) on the vertical axis (in purple).

However, there are two special edge cases:

- If the segment is vertical (its x coordinates for both endpoints are the same), then its projection on the horizontal (X) axis is a point.

- If the segment is horizontal (its y coordinates for both endpoints are the same), then its projection on the vertical (Y) axis is a point.

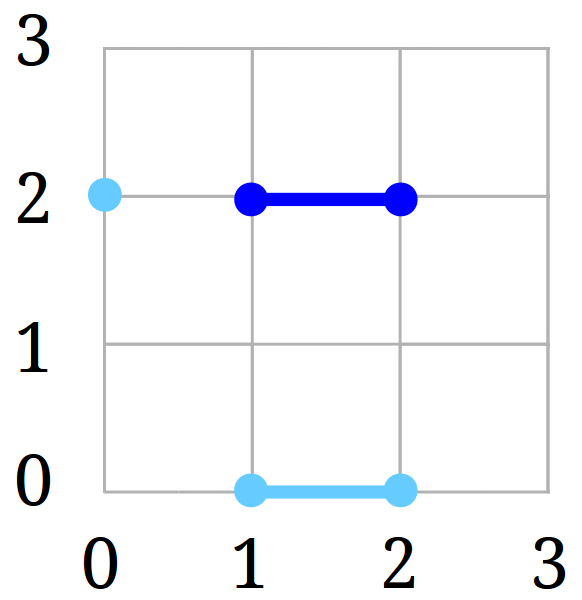

For example, in the figure at the right we have a segment with endpoints (1, 2) and (2, 2). (This segment will be referred to as “the blue segment” later on.) Its projection on the horizontal axis is another segment, but its projection on the vertical axis is the point with coordinates (0, 2).

Therefore, the result of either projection operation in terms of the data structures defined in the code snippet above can be either a Segment or a Point2D. And, as it so happens, one cannot have a function return different result types in a strongly typed language such as C.

The solution: unions

Enter unions. They allow you to store different data types in the same memory space, but not at the same time. Like a struct, a union has members, but only one of them can store information at any given time. Why is this interesting, you ask? Here’s why: a union has the size of its largest member. This is very important when aiming to reduce the memory footprint of an application.

Here is a first take for a union that stores the result of a segment projection operation:

1

2

3

4

typedef union {

Segment segment;

Point2D point;

} _Projection;

Using the _Projection union above, when we project the red segment on the X and Y axes, we store the resulting segment in the segment member of the union. Conversely, when we project the blue segment on the X and Y axes, we store the resulting point in the point member of the union.

That’s great, but how do we know in which member of the union our valuable information is being stored? We need some sort of hint to figure out if a given _Projection variable contains a segment or a point. This hint commonly goes by the name of flag and requires a structure of its own to live in. We cannot simply add the flag to the _Projection union directly since this would mean that such a union can only store one of three possible values: a segment, a point or a flag. For this reason we wrap the whole _Projection union into a struct, as follows:

1

2

3

4

typedef struct {

_Projection proj;

bool is_segment;

} Projection;

(Don’t forget to #include <stdbool.h> for the bool type.)

So how does this thing work? We could write something like the following:

1

2

3

4

Projection p;

p.is_segment = false;

p.proj.point.x = 0;

p.proj.point.y = 0;

Even better: anonymous unions

I think you will agree that the access to proj is both tiring and ugly. We can avoid it if we nest the union directly inside the struct, without giving it a name. This is called an anonymous union. The catch is that anonymous unions are only available starting with C11. So let’s rewrite the data structure:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

typedef struct {

union {

Point2D point;

Segment segment;

};

bool is_segment;

} Projection;

It is now much easier to access, say, the point member:

1

2

3

4

Projection p;

p.is_segment = false;

p.point.x = 0;

p.point.y = 0;

Practical usage

Great, so how do we use this? Let’s look at one of the two projection functions, for instance the one that projects a given segment on the vertical (Y) axis. We could write it as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

/*

* Projects 'segment' on the vertical (Y) axis and returns the projection

* result: a Point2D if 'segment' is horizontal, or another Segment otherwise.

*/

Projection vertical_projection(Segment segment)

{

Projection result;

if (segment.start.y == segment.end.y) {

result.is_segment = false;

result.point.x = 0;

result.point.y = segment.start.y;

} else {

result.is_segment = true;

result.segment.start.x = result.segment.end.x = 0;

result.segment.start.y = segment.start.y;

result.segment.end.y = segment.end.y;

}

return result;

}

Testing the solution

Let’s test the vertical_projection() function on the red and blue segments above.

The first thing to do is to define two general functions that will test whether a Projection respectively contains the specified Segment or Point2D. These functions will involve assertions, so we will need to #include <assert.h>. If an assertion fails, the program execution is aborted.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

/* Checks whether the Projection contains the specified Point2D. */

void assert_projection_is_point(Projection result, Point2D point)

{

assert(!result.is_segment

&& result.point.x == point.x

&& result.point.y == point.y);

}

/* Checks whether the Projection contains the specified Segment. */

void assert_projection_is_segment(Projection result, Segment segment)

{

assert(result.is_segment

&& result.segment.start.x == segment.start.x

&& result.segment.start.y == segment.start.y

&& result.segment.end.x == segment.end.x

&& result.segment.end.y == segment.end.y);

}

These two general functions may now be used to test the specific examples we’ve seen above.

The red segment must have the segment with endpoints (0, 1) and (0, 2) as its projection on the vertical axis (in purple in the figure):

1

2

3

4

5

Segment red_segment = {{1, 1}, {2, 2}};

Segment red_v_proj = {{0, 1}, {0, 2}};

assert_is_segment(vertical_projection(red_segment), red_v_proj);

The blue segment must have the point with coordinates (0, 2) as its projection on the vertical axis:

1

2

3

4

5

Segment blue_segment = {{1, 2}, {2, 2}};

Point2D blue_v_proj = {0, 2};

assert_is_point(vertical_projection(blue_segment), blue_v_proj);

Notes

- These examples do not use pointers as it was beyond the scope of the class.

- No student fell asleep during the class but they were all eerily quiet. I think they might find nested structures disturbing.

- The full implementation is available on GitHub.

Comments powered by Disqus.